Plastic recycling | The toxic truth about recycled plastic

Recycling has long been pushed as the natural solution to plastic pollution. But the truth is, plastic recycling only escalates the problems it sets out to solve, creating new dangers for the environment and threatening human health.

As more information about plastic recycling comes to light, it has become clear that it will not solve plastic pollution, with recycled plastics actually more toxic than virgin plastic.

What has been framed as the answer to the plastic problem is unravelling as another example of industry greenwashing, serving only to delay the necessary transition to alternative materials.

Continue reading to learn more about the great deception of plastic recycling or navigate to a particular section of the article using the links below…

Plastic recycling process

Learn about the different methods for recycling plastic and find out how much plastic is actually recycled globally.

Read MoreIssues with plastic recycling

Read up on the issues associated with plastic recycling, from carbon emissions to microplastics leaching.

Read MoreAlternatives to plastic

Discover alternative materials with proven sustainability credentials that can be used in place of plastics.

Read MoreHow is plastic recycled?

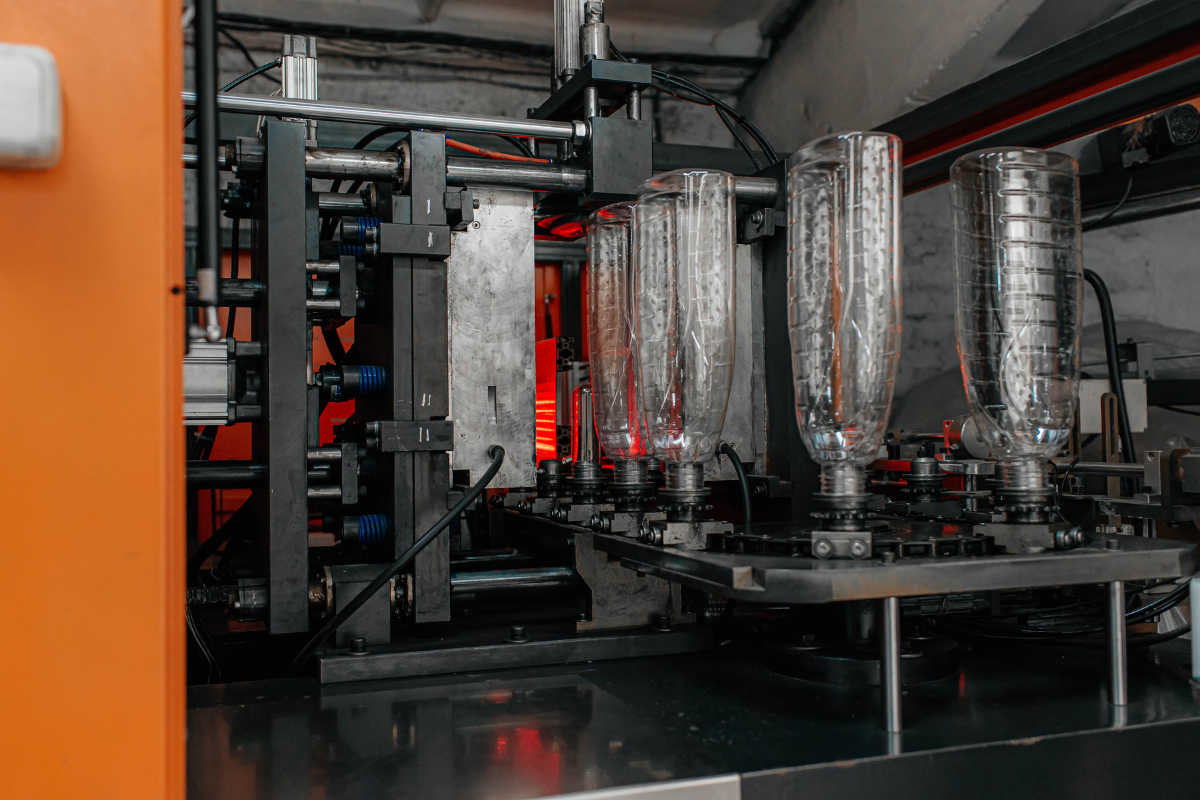

Plastic can be quite difficult to recycle, and the process varies depending on the material, but generally plastic waste is collected and sent to recycling centres where it is separated, shredded and then melted down to a liquid state ready for casting into a mould.

The process is time-consuming and emissions-intensive, with it being far easier to produce new, virgin plastic than recycle plastic waste. This goes a long way to explaining why adoption rates for plastic recycling have been slow to say the least.

Recycled plastic accounts for just 6% of global plastic production and only 9% of plastic is actually recycled. Around half of it ends up in landfill, a fifth is incinerated and the remainder is mismanaged, being left to leach into the environment.

Of this mismanaged waste, much of it ends up in the ocean, with estimates indicating that between 8 million and 11 million tons of plastic enter the ocean every year.

Recycling is the only method that could theoretically make plastics sustainable, so naturally has become key to the long-term future of the plastic industry.

At present, however, there is little evidence to suggest plastic recycling is having a positive impact, with efforts to develop a recycling process that is legitimately safe and sustainable so far proving unsuccessful.

Learn more about the myth of plastic recycling below

What are the different types of plastic recycling?

There are two main types of plastic recycling: mechanical and chemical. Most plastic is recycled mechanically through a process of sorting, washing, grinding and re-granulating waste plastics. Chemical recycling is a more recently developed method that involves breaking down the chemical structure of plastic using heat or chemical processes.

Mechanical recycling

Mechanical recycling refers to a multi-stage process of sorting, cleaning and shredding waste plastic into tiny particles, ready for melting down into new plastic. It’s commonly used to recycle PE and HDPE, with typical end-products being plastic bottles, carrier bags and cosmetics bottles.

The main drawback with mechanical recycling is that it changes the molecular structure of the plastic, in turn reducing its material integrity. As a result, recycled plastic is routinely mixed with virgin plastic to make new products, and even then, it can still only be recycled two or three times.

Chemical recycling

Chemical recycling (sometimes referred to as advanced recycling) has been pushed by the plastic industry as a solution to the shortcomings of mechanical recycling, supposedly increasing both the quality of recycled plastic and the number of plastic materials that can be recycled.

This method draws on a range of complex chemical processes, including pyrolysis, gasification and depolymerisation, to break down plastics to the molecular level for use as building blocks for new plastic products.

In reality, chemical recycling is yet to be implemented at scale, currently accounting for a tiny fraction of overall plastic recycling. Only certain plastics can be recycled using chemical processes and where this is the case the process is not always successful.

A report from Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network found that this purportedly advanced method of plastic recycling hasn’t worked for decades, and only produces small amounts of material that can actually be recycled, while also generating considerable amounts of hazardous waste.

And even if these issues could be resolved, chemical recycling would still be plagued by many of the same flaws faced by mechanical recycling. Neither method removes the toxins used to make the plastics in the first place. On top of that, the process still alters the plastic in a way that will always reduce its quality and limit its number of uses.

The plastic industry has long been aware of these facts, as a recent report from the Centre for Climate Integrity documents, but this has not stopped it from funnelling huge amounts of resources into a campaign of fraud and deception to promote recycling as a viable solution to the plastic problem.

Compare plastic recycling to copper recycling below

What are the disadvantages of recycling plastics?

So far, it’s fair to say plastic recycling is yet to resolve the many health and environmental issues associated with plastic. In fact, it has actually brought about new challenges and risks:

- Plastic recycling is emissions-intensive

- Recycled plastic is more toxic than virgin plastic

- Plastic can still only be recycled a few times

Plastic recycling harms the planet

While all recycling processes release emissions, plastic recycling in particular is known for being a heavy polluter. It involves a lengthy process of sorting and cleaning before any recycling of waste products can take place.

The recycling process itself uses lots of electricity and natural gas to heat the plastic waste and spark chemical reactions. Plastics that are harder to recycle (like PVC and PP) are subject to different processes and will use considerably more energy.

While chemical recycling has been said to be better for the environment than mechanical recycling, one study concluded that its climate change impact is actually about 7% higher. Another study found that plastic recycling has a CO2 equivalent of 1.3 GHG, more than alternatives like glass, aluminium and steel.

Phasing out plastics will not only reduce emissions associated with the plastic recycling process. By switching to alternative materials that can be recycled infinitely, the demand for virgin plastics will decrease and so too will the need for emissions-intensive disposal methods like incineration.

Learn more about the environmental impact of plastics below

Recycled plastics threaten human health

Plastics are made up of a multitude of toxins that don’t just disappear after recycling. In fact, recent research suggests plastic may grow in toxicity each time it is recycled.

A landmark report from Greenpeace found that recycled plastics contain higher levels of several highly toxic chemicals including various carcinogens, brominated and chlorinated dioxins, as well as numerous endocrine disruptors.

Research from the University of Gothenburg came to similar conclusions, finding hundreds of toxic chemicals in test samples of recycled plastic from recycling plants in 13 different countries.

This is hardly surprising when you consider that more than 13,000 chemicals have been identified as being associated with plastics, with more than a quarter of these being deemed hazardous by the United Nations.

Several real-life examples already evidence the potentially fatal impacts of these toxins. Melted plastics pipes were found to leach toxic chemicals into the water supply of at least two California communities following wildfires in 2017 and 2018, with one sample showing the carcinogen benzene to be at 40 times above the state’s drinking water standard.

In the UK, more than a dozen firefighters tackling the tragic Grenfell fire in 2017 have been diagnosed with terminal cancers directly linked to toxic fumes from burning plastic cladding.

Another report from CuSP member, Safe Piping Matters, found that common piping materials PVC and PE plastic degrade “relatively quickly” and release a wide range of hazardous plastic particles including aldehydes, ketones and esters into the water.

Across the built environment, work must be done to reduce our reliance on plastics and limit the already significant exposure of humans to ingested microplastics that are infiltrating water supplies, food systems and the air.

Learn more about the health risks of plastics below

Recycled plastics have no place in the circular economy

Plastic recycling does not form part of a circular living model because it continually degrades the overall quality of plastic to the point where it can no longer be used. In fact, most plastic can only be recycled a single time.

With mechanical recycling, the polymeric chain that holds that plastic together degrades each time the plastic is melted and processed. On top of this, it’s virtually impossible to separate plastics entirely, so the recycled plastic is likely to have a slightly alerted set of properties to the original.

Chemical recycling has been pushed by the plastic industry as a way to retain the quality of virgin plastic through the recycling process, however this vision currently has little grounding in reality.

A report from Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network on the current state of chemical recycling the in the US found that there were just 11 chemical recycling facilities operating in the US.

If all of these facilities were running at full capacity, they would only be able to handle less than 1.3% of plastic waste. The report describes chemical recycling as “rarely successful in turning old plastic into new plastic”, with the technology just another example of industry greenwashing designed to legitimate the continued use of plastics.

The bottom line is that the vast majority of recycled plastic still comes from mechanical recycling, a process completely at odds with the circular economy because it can only be done a few times before the quality of the plastic decreases to the point where it can no longer be used.

Learn more about the importance of the circular economy below

Alternatives to recycled plastics

In a world where countries and economies are looking to decarbonise, plastic remains one of the main stumbling blocks to a greener future. In 2019, plastics were responsible for around 3.4% of global emissions, and with plastic production set to triple by 2060, this figure looks likely to rise.

The projections are concerning, and greenwashing efforts have largely been successful in masking the true extent of the plastic problem, however the good news is that alternatives with proven sustainability credentials and established recycling infrastructures are readily available.

In the packaging sector – the biggest end user for plastic – glass, paper and biodegradable packaging made with plant-based materials all offer a more sustainable and circular alternative to single-use plastic.

Plastic is also used in building and construction for everything from cables, pipes and guttering to doors, windows and insulation. Timber and aluminium serve as good alternatives for windows and doors, while natural substitutes like cellulose or wood fibre can be used in insulation.

When it comes to plumbing and guttering, metal alternatives like copper and cast iron can be recycled an infinite number of times and are also likely to last longer, reducing the need for repairs and replacements.

Many plastic alternatives – and particularly the metals – have been recycled successfully for decades using proven techniques. In the case of copper, recycled copper currently accounts for around half of copper usage in Europe, with at least 65% of all copper mined since 1900 also remaining in use.

Compared to plastics, which by their nature are difficult to recycle, scrap copper can easily be recycled by separating it from other materials and then melting it down to a liquid state, ready for recasting using a mould. The process is always succcessful — unlike mechanical and chemical recycling of plastics — and has less of an impact on the environment.

Although alternative materials are readily available, plastic continues to be used ahead because it is cheaper. But this reasoning is short-sighted and only benefits the plastic manufacturers themselves.

Ultimately, there is little to gain from plastic recycling as the material will eventually degrade and become unusable. With circular materials, however, there is a clear incentive to recycle as it yields a high-quality product that is as good as new.

Learn more about the benefits of copper over plastic below

Copper: the sustainable choice

The time has come to phase out plastics in favour of recyclable materials that meet the needs of the circular economy. As one of the oldest and most trusted materials around, copper provides a ready-made alternative to plastic for use in plumbing and construction.

Unlike plastic, copper can be recycled an infinite number of times without any loss of quality, and an established recycling infrastructure for collecting, sorting, melting down and recasting scrap copper is already in place, meaning there is a clear incentive and reward for recycling.

With alternatives like copper readily available, there’s little reason to continue using plastics. So far, plastic recycling has increased our reliance on the material without resolving its many issues, delaying the one piece of action that will spark meaningful change: to phase out plastics entirely.

Fed up with the plastics greenwash? Want to learn more about the role of copper in shaping a more sustainable future? Check out some of our other articles or subscribe to our newsletter below.